ohm

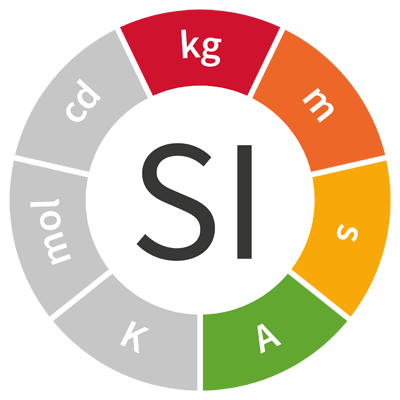

SI coherent derived unit with special name and symbol

| Name | Symbol | Quantity | Base units |

| ohm | Ω | electrical resistance | kg m2 s−3 A-2 |

The ohm, symbol Ω, is the SI coherent derived unit of electrical resistance. It is the special name for the kg m2 s−3 A-2. The ohm, symbol Ω, is the SI coherent derived unit of electrical resistance. It is the special name for the kg m2 s−3 A-2.One ohm is defined as the electrical resistance between two points of a conductor when a constant potential difference of one volt, applied to these points, produces in the conductor a current of one ampere, the conductor not being the seat of any electromotive force. |

|||

| Definition | h e-2 | ||

|

|||

The ohm is named after the German physicist Georg Simon Ohm.

Resistance

The electrical resistance of an object is a measure of its opposition to the flow of electric current. The resistance of an object is defined as the ratio of voltage across it to current passing through it:

Using SI coherent units,

- R is the resistance of the object in ohms, symbol Ω,

- V is the voltage across the object in volts, symbol V,

- I is the current through the object in amperes, symbol A.

The electrical resistance of an object depends on:

- the material it is made of,

- cross-sectional area,

- length.

For example, a thick copper wire has a lower resistance than a thin copper wire.

Ohm’s law

Ohm’s law states that the current through a conductor between two points is directly proportional to the voltage across the two points, with the proportionality constant being defined as the resistance of the conductor.

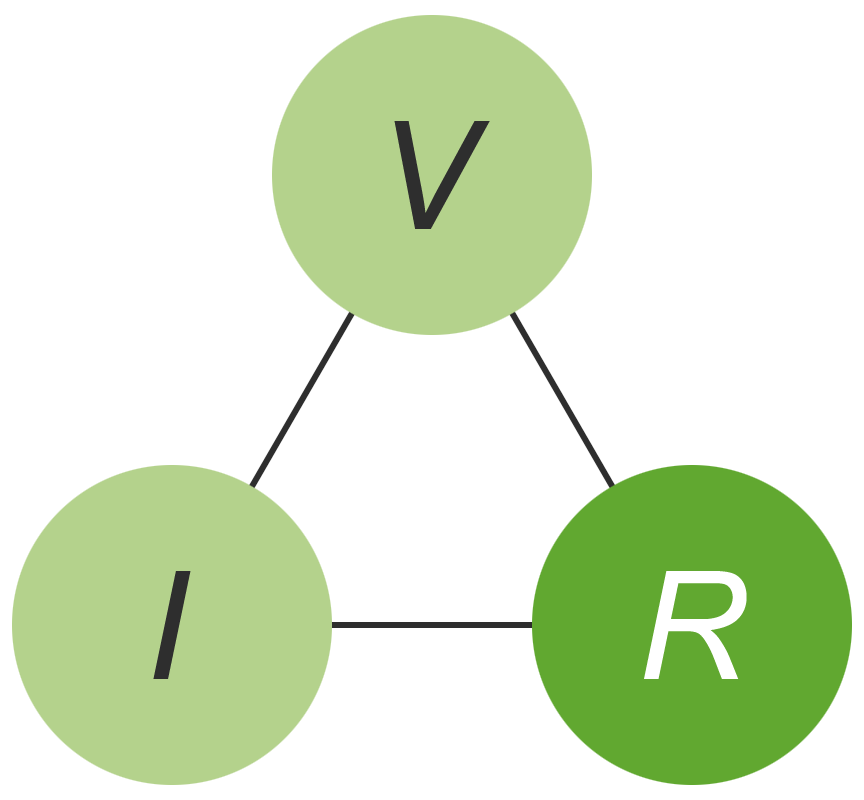

The relation between voltage, V, current, I and resistance, R can be represented mathematically by either of the following equations:

Arranging the symbols V, I and R in the form of a triangle, provides a useful mnemonic for remembering the relation between these three quantities.

|

|

|

The quantum Hall effect

If a current of ultracold electrons, flowing in the form of a sheet thin enough to be regarded as two-dimensional, is exposed to a strong magnetic field perpendicular to the sheet, electrical resistance across the width of the current stream develops in exactly quantized steps.

The magnitude of the resistance at each quantized step, RQHR, is proportional to the quotient h⁄e2, and indirectly proportional to the step number i, where:

Using SI coherent units:

- RQHR is the quantum Hall resistance in ohms, symbol Ω,

- i is the step number in integers,

- h is the Planck constant in joule seconds, symbol J s,

- e is the elementary charge in coulombs, symbol C.

The quotient h⁄e2 is equal to the von Klitzing constant, RK, named after German physicist Klaus von Klitzing.

Resistance values realised using the quantum Hall effect can be reproduced with relative uncertainties of one part in a billion. For this reason, the effect is used as the basis for constant reference resistors for calibrations in national metrology institutes all over the world.

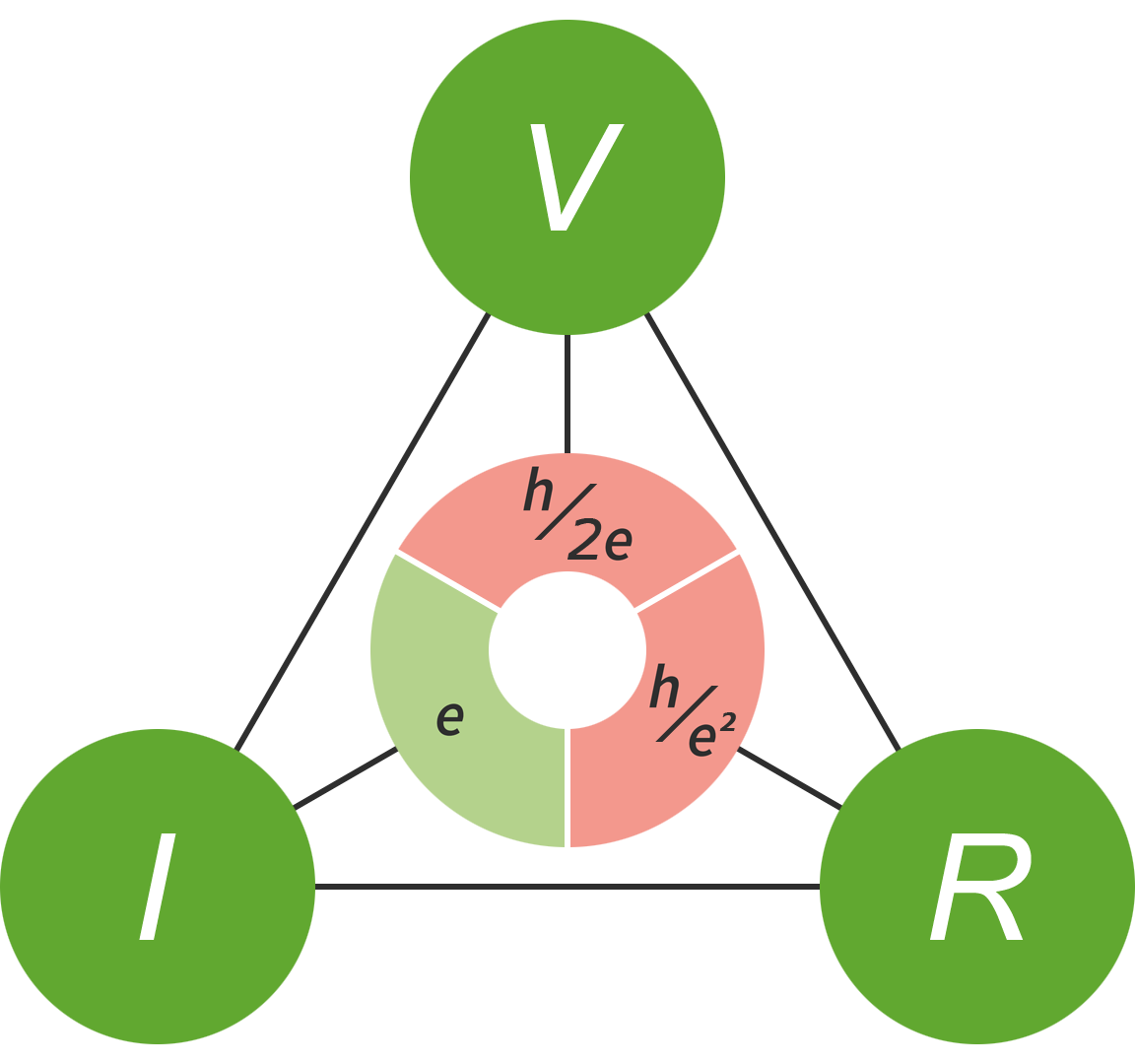

The quantum metrology triangle

The generation of standard resistors, using the quantum Hall effect, is one of three macroscopic quantum techniques that collectively form what is known as the quantum metrology triangle. The other two are the generation of standard voltages, using the Josephson effect, and the generation of standard electric currents using single electron pumps.

|

Measuring quantities at any two corners of the quantum metrology triangle allows the third quantity to be calculated to a high degree of precision via Ohm’s law:

where:

- VJVS is a standard voltage generated using the Josephson effect,

- ISEP is a standard current generated using a single electron pump,

- RQHR is a standard electrical resistance generated using the quantum Hall effect.

The quantum metrology triangle relates three physical constants; the Josephson constant, KJ, the von Klitzing constant, RK, and the elementary charge, e.

Resistivity

The resistance of an object made of a given material is directly proportional to the length of the object, and inversely proportional to its cross-sectional area;

Using SI coherent units, the proportionality constant, ρ, is the resistivity of the material in ohm metres, symbol Ω m:

Temperature

At temperatures of around 20 °C, an increase in temperature typically results in an increase of a metal’s resistivity, and a decrease in a semiconductor’s resistivity. This effect is made use of in the design of resistance thermometers, or thermistors.

Strain

When a conductor is placed under tension, leading to strain in the form of stretching of the conductor, the length of the section of conductor under tension increases and its cross-sectional area decreases. Both these effects contribute to increasing the resistance of the strained section of conductor. Under compression, the resistance of the strained section of conductor decreases. This effect is made use of in the design of strain gauges.

Photoresistance

Some resistors, particularly those made from semiconductors, exhibit photoconductivity, That is, the magnitude of their resistance depends on the amount of incident light. Resistors made from such materials are called photoresistors. This effect is made use of in basic light detectors.

Impedance

Impedance extends the concept of resistance to AC circuits, and possesses both magnitude and phase, unlike resistance, which has only magnitude. When a circuit is driven with direct current (DC), there is no distinction between impedance and resistance. Resistance can be thought of as impedance with zero phase angle.

Superconductivity

Superconductors are made of materials that have zero resistance.

Superconductors only exhibit superconductivity at very low temperatures. Metallic superconductors generally require cooling to temperatures near 4 K with liquid helium. Some “high temperature” ceramic superconductors remain superconductive near 77 K, and thus cooling with liquid nitrogen is sufficient.

When a current passes through a superconductor, there is no joule heating, and no dissipation of electrical energy. Superconductors would therefore be ideal for power transmission, were it not for the impracticalities of their low temperature requirements.