ampere

SI base unit

| Name | Symbol | Quantity | |

| ampere | A | electric current | |

The ampere, symbol A, is the SI base unit of electric current. The ampere, symbol A, is the SI base unit of electric current.The ampere is defined by taking the fixed numerical value of the elementary charge e to be 1.602 176 634 × 10−19 when expressed in the unit C, which is equal to s A, where the second is defined in terms of ΔνCs. |

|||

| Definition | |||

The ampere is named after the French mathematician and physicist André-Marie Ampère (1775 – 1836).

The relation between the caesium frequency, ΔνCs, and the elementary charge, e, forms the basis for the definition of the unit of electric current, the ampere.

The definition of the ampere implies the exact relation:

Inverting this relation gives an exact expression for the ampere in terms of the defining constants e and ΔνCs :

The effect of this definition is that one ampere is the electric current corresponding to the flow of 1⁄1.602 176 634 × 10–19 elementary charges per second.

Electric current

An electric current, I, is the rate of flow of electric charge, Q, past a given point in a given time, t.

The SI unit of charge, the coulomb, symbol C, is the amount of electric charge carried in one second by a current of one ampere. Conversely, a current of one ampere is one coulomb of charge passing a given point in one second:

An electric current consists of the movement of particles called charge carriers.

- In a metal wire, charge is carried by the loosely bound electrons of metal atoms.

- In an electrolyte, charge is carried by ions (charged atoms or molecules).

- In an ionised gas, or plasma, charge is carried by ions and electrons.

Ohm’s law

An electric current, I, flows between two points of a conductor when a potential difference, or voltage, V, is applied across the two points.

Ohm’s law states that the current through a conductor between two points is directly proportional to the voltage across the two points, and indirectly proportional to the resistance of the conductor.

Using SI coherent units, the proportionality constant is 1, Thus:

where:

- current, I, is measured in amperes, symbol A,

- voltage, V, is measured in volts, symbol V,

- resistance, R, is measured in ohms, symbol Ω.

The relation between voltage, V, current, I and resistance, R can be represented mathematically by either of the following equations:

Arranging the symbols V, I and R in the form of a triangle, provides a useful mnemonic for remembering the relation between these three quantities.

|

|

|

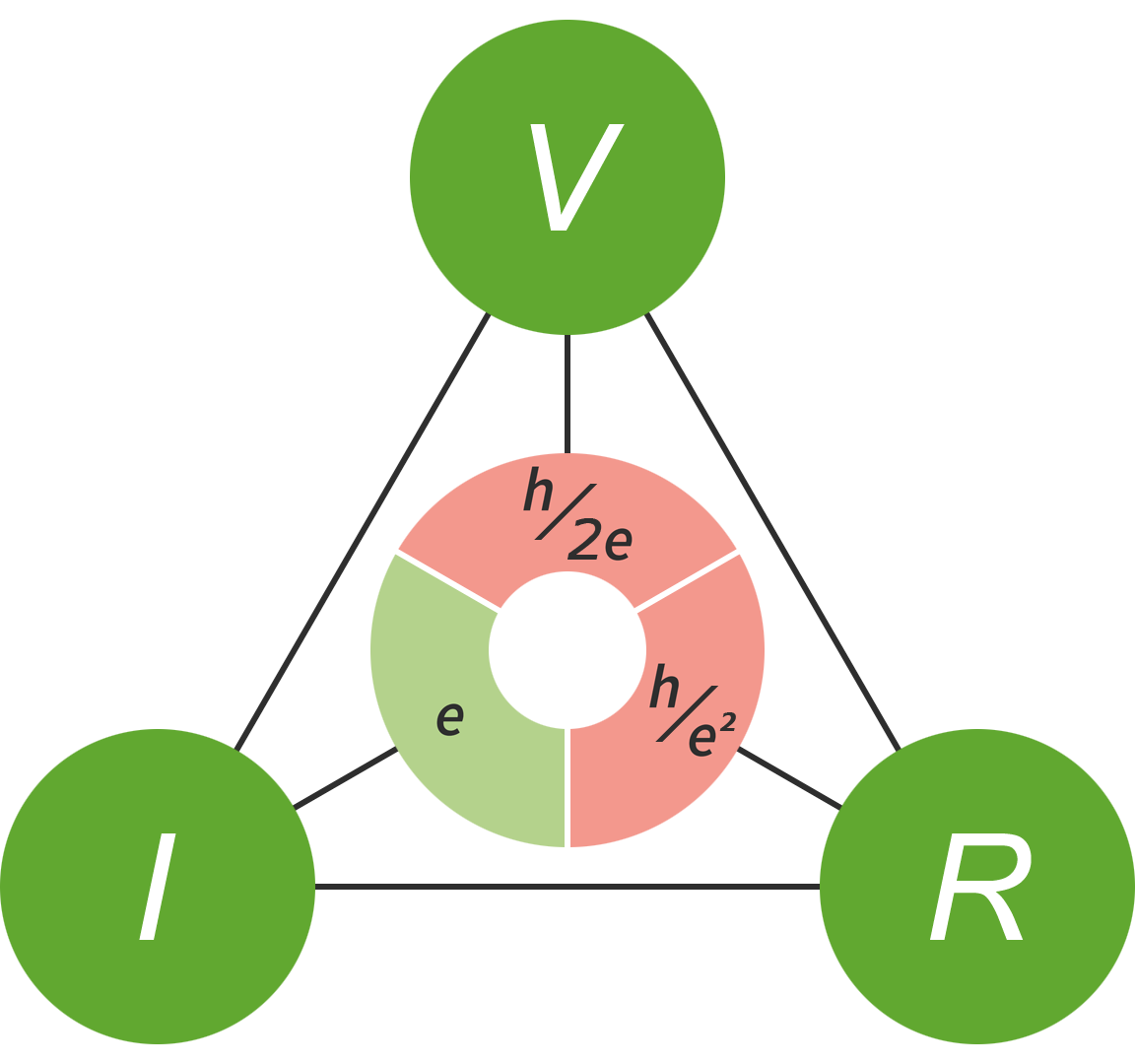

The quantum metrology triangle

The generation of standard electric currents, using single electron pumps, or SEPs, is one of three macroscopic quantum techniques that collectively form what is known as the quantum metrology triangle. The other two are the generation of standard voltages, using the Josephson effect, and the generation of standard resistors, using the quantum Hall effect.

|

Measuring quantities at any two corners of the quantum metrology triangle allows the third quantity to be calculated to a high degree of precision via Ohm’s law:

where:

- VJVS is a standard voltage generated using the Josephson effect,

- ISEP is a standard current generated using a single electron pump,

- RQHR is a standard electrical resistance generated using the quantum Hall effect.

The quantum metrology triangle relates three physical constants; the Josephson constant, KJ, the von Klitzing constant, RK, and the elementary charge, e.

Joule’s first law

Joule heating, also known as resistive heating, is the process of heat dissipation by which the passage of an electric current through a conductor increases the internal energy of the conductor, converting thermodynamic work into heat. Joule’s first law states that the rate of heat production, or resistive heating power P, of a conductor is directly proportional to the product of the square of the current I and its electrical resistance R.

Using SI coherent units, the proportionality constant is 1, Thus:

where

- power, P, is measured in watts, symbol W,

- current, I, is measured in amperes, symbol A,

- resistance, R, is measured in ohms, symbol Ω.

Resistive heating is utilised in incandescent light bulbs and electric fires.

Electromagnetism

Electric current produces a magnetic field. The magnetic field can be visualised as a pattern of circular field lines surrounding the wire.

In an electromagnet, a current passing through a coil of wire produces a magnetic field with a pattern of field lines resembling those of a permanent magnet. The magnetic field produced by an electric current persists only as long as there is current.

Electromagnetic induction

Magnetic fields can also be used to make electric currents. When a changing magnetic field is applied to a conductor, an electromotive force (EMF) is induced, which starts an electric current, when there is a suitable path.

Radio waves

Alternating currents at certain frequencies generate radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic radiation like light but at lower frequencies. They carry energy and travel at the speed of light. Radio waves can in turn induce an alternating electric current in a conductor at a distance. This effect is utilised in radio communication in which radio waves are modulated to carry information, or a signal.

Ampère’s force law

Ampère’s force law states that there is an attractive or repulsive force between two parallel wires carrying an electric current. Prior to 2019, this force was used in the definition of the ampere.

Examples of electric currents

| Source | Current |

| 230 V AC, 2 kW kettle | 9 A |

| 230 V AC, 4 kW immersion heater | 20 A |

Electric current is generally measured using an instrument called an ammeter.